How to Walk Away From Fear, and Toward Love.

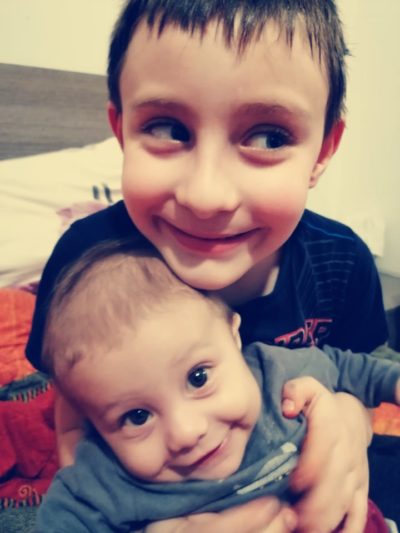

Two emotions swirl in the heart of just about every parent: love and fear.

If you are standing near a busy road, and your young child suddenly runs toward an oncoming truck, fear quickly becomes the loudest of the two. And this is a good thing! Your brain’s threat detector, the amygdala, sends out signals that launch your body into fight-or-flight mode. Before your rational brain even has time to process what’s happening, you are flooded with adrenaline and surge with energy. You sprint faster than you thought you could toward your little one and snatch your child just in time. It takes a while for your heart rate and blood pressure to come back down. You may feel shaky or enraged. Perhaps you cry. This is all part of your body’s natural and necessary return to homeostasis—to a state of balance and calm. In this instance, your fear has helped to save your child’s life. Your fear has been in service of your love.

What happens, though, when a threat doesn’t go away? If you are the parent of a child with PFIC, it isn’t just a single truck that you fear. The threat doesn’t simply roll past and disappear into the horizon. A better metaphor for your reality may be this: For no good reason at all, your child is compelled to walk on the shoulder of a highway. You have no control over this basic fact—at least not right now. Being the loving parent that you are, you walk next to your kid, hand in hand. Maddeningly, you are not permitted to stand between your child and the traffic. Rather, you must stay on the outside, operating as a guide and a source of support and comfort, rather than as a literal shield. You wish you could be a shield.

If fear feels like your constant companion, that’s understandable. Fear is a normal response to illness, and so ongoing fear is a normal response to ongoing illness. Your fear is just a natural outgrowth of the desire to protect your child. Sometimes, though, fear can become so big, so constant, and so overwhelming that it constitutes its own problem. Sometimes, fear buries the more positive and joyful feelings associated with love. Let’s think back to the road metaphor for a moment. When the traffic diminishes or disappears (let’s say your child is experiencing

some symptom relief from a new treatment), what happens to your fear? Does it diminish? Disappear? Or does it retain its chokehold? Are you able, in such moments, to simply enjoy the feeling of your child’s hand in yours? Or are you swiveling your head in all directions, scanning for the next threat? How loud, close, or fast does the traffic have to be for fear to dominate your experience? How quiet, distant, or slow must the traffic be for your feelings of love to outshine your feelings of fear?

Whatever your answers to these questions are, you can begin taking baby steps in the direction of love–and away from fear.

This is true both pre- and post-transplant. It is true in the wake of a fresh diagnosis, and it is true in the aftermath of an unsuccessful treatment. It is true even in the middle of the darkest, most sleepless night. We can all move, one small step at a time, out of fear and into its opposite–love.

What does this look like?

Let’s imagine a moment in which you’re snuggling with your child, but your mind is disconnected from what your body is doing. It is spiraling with worry and fear. As soon as you notice that your fear has taken you away from your child and from the moment you’re in, you have an opportunity to baby step your way back. This simple noticing is step one.

Step two could be a deep breath in and a long, slow breath out. Perhaps you count to four on your inhale and six on your exhale. When we lengthen our exhalation so that it’s longer than our inhalation, we signal to our brain that we’re safe. Just a few of these mindful, slow breaths can be enough to begin calming our ever-vigilant threat-detecting mind.

Once you’ve noticed your fear and greeted it with a few deep, slow breaths, begin noticing the feeling of being in your own body. More specifically, you might notice the sensation of your child’s hand in yours or the warmth of their body as it leans into you. For just a moment, give yourself fully to these sensations. Affectionate physical touch releases oxytocin, the ‘love hormone’, and can bring with it feelings of love and well-being. These are not just the opposite of fear; they are the antidote to fear. Love won’t wipe out fear permanently, but for one micro-moment at a time, it can replace fear with something infinitely more nourishing. Baby steps, remember?

Every time that you notice the spiral and come back to the simple experience of being in this moment and connecting with your child—whether that means cuddling with them, making eye contact, laughing together, or listening deeply to what they have to say—you are baby-stepping out of fear and into love.

Here are a few more small steps you can try:

- When you feel your stress building or refusing to abate, ask yourself this simple question: “Love or fear?” Notice what feels fearful inside of you. Then notice the love that is hiding beneath it. Give your attention to that feeling of love.

- Open yourself up to receiving care, affection, and love from others. Be willing to tell a trusted friend or family member what you are feeling and how they can help—“I’m terrified, and I know you can’t fix it, but I could really use a hug.”

- Notice the small ways in which others are already showing you love. Include your love for yourself in this! You can jot these down or just take a moment to observe and appreciate each warm smile, each small favor, each kind word, and each gentle caress.

- Bookend your day with positive and loving thoughts. Before you climb out of bed, take a deep breath and connect with a loving thought, feeling, or intention. At the end of the day, jot down a positive or loving thought—something you would like to dream about, perhaps—and tuck it beneath your pillow.

- Seek professional help. Getting help is often the bravest, most loving thing we can do. Find an empathic therapist. You can also join one of the PFIC Network’s PFIC support groups.

You won’t completely vanquish your fear (if you do, please teach the rest of us how!), but by replacing two seconds of fear with two seconds of love, you’ve accomplished something meaningful. Over time, perhaps you manage to replace two minutes of fear or even two hours of fear with something lighter, softer, and more loving—something that nourishes you and your child.