Life with PFIC is hard. This is true whether you are a patient, a family member, or a friend. When life’s challenges feel overwhelming, we humans tend to default to a handful of fairly predictable but rather unhelpful responses. We might ruminate, thinking obsessively about the source of our pain. We might catastrophize, imagining worst case future scenarios. We might blame ourselves or beat ourselves up for not handling our problems perfectly. Perhaps we go into hyperdrive, attempting to control every detail of our lives. Or maybe we shut down. None of these responses are especially helpful in the long run, but all of them are completely normal.

The suffering that is directly caused by PFIC—for example, the itch, the struggle to pay down medical bills, the stress of hospital stays, and the pain of invasive treatments—is what psychologists sometimes refer to as clean pain. It’s the hand that you’ve been dealt and as such, is largely beyond your control. It’s the pain that anyone would experience in your circumstances.

We humans have big, amazing brains with powerful problem-solving capacities. This is great—except that we sometimes use our incredible intellects in ways that cause us more suffering. The additional suffering that we experience as a result of our thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors is called dirty pain. The miserable sensation of itch is clean pain. The belief that “I can’t bear this for another second” and the feelings of despair that follow on the coattails of such a belief are an example of dirty pain. The loss and grief of giving up a career or hobby that you love because your child needs more of your time and energy is clean pain. (Clean pain can be big pain!) The belief that “This is so unfair” or “My hopes of happiness are ruined” is dirty pain.

‘Dirty’ might sound like a pejorative label. We all experience dirty pain, though. When you notice that some of your pain isn’t strictly necessary, this is not a reason to beat yourself up. Quite the opposite—it can be a reason to celebrate! If your pain is ‘dirty’ or unnecessary, then you can choose to set it down. Will you accomplish this all at once? Probably not. Is it something that you can learn to do? Absolutely.

Much of our dirty pain is tied to our failure to give ourselves permission to honor our own needs. As you read through the list below, notice if some of these ‘permission slips’ trigger either a feeling of relief or a feeling of resistance in you. Either of those could be an indication that you’ve landed in a patch of dirty pain—a place where, by giving yourself permission to think or feel or do things differently, you might be able to set down a piece of your suffering.

- You have permission to feel the full range of your emotions. You have permission to grieve, permission to rage, permission to laugh, permission to dance, and permission to cry.

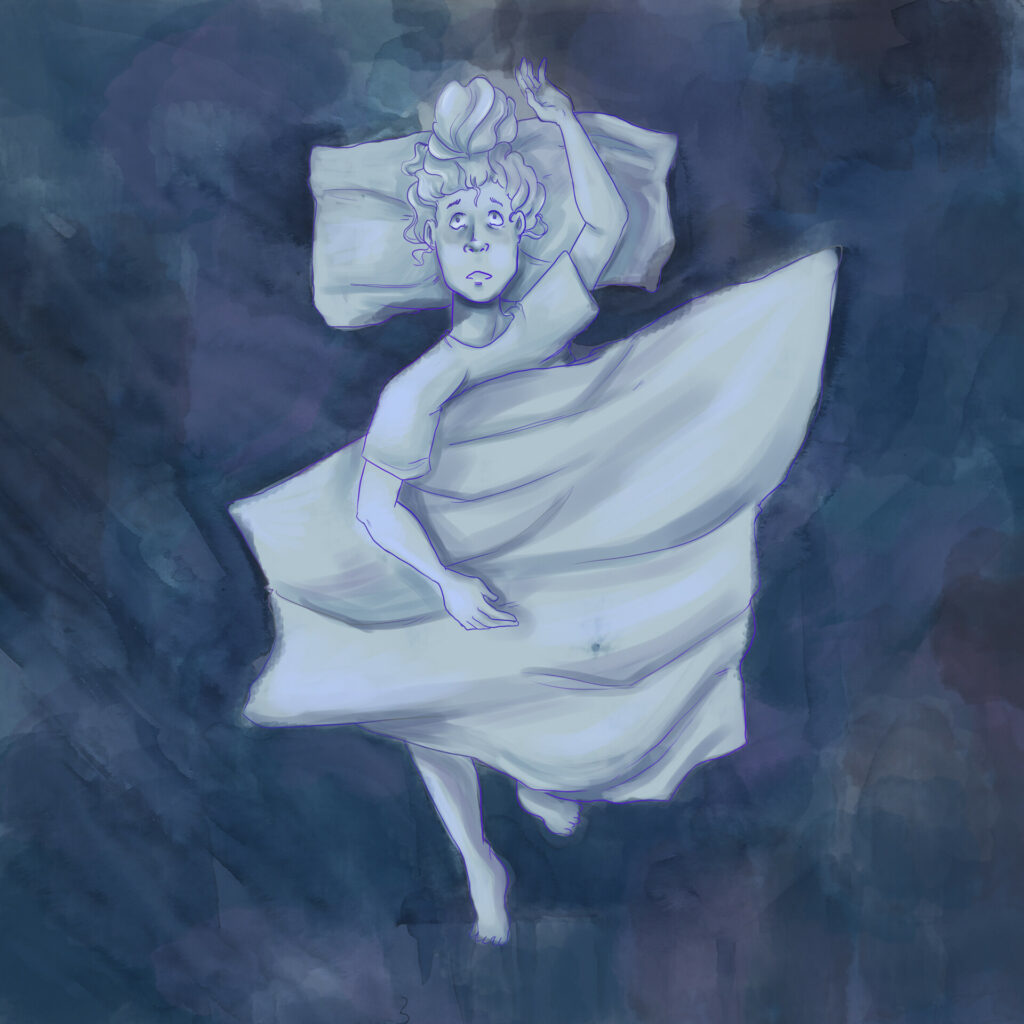

- You have permission to feel numb. You have permission to just go through the motions. You have permission to be in survival mode. You won’t be in this place forever, but if it’s where you are now, then you have permission to be there.

- You have permission to feel overwhelmed. And whether or not you feel overwhelmed, you have permission to say “no” to anything that doesn’t feel like a resounding “yes.” You have permission to turn down obligations and opportunities. You have permission to let things slide from your too-full plate.

- You have permission to ask for help, and you have permission to be choosy about who’s help you want and trust.

- You have permission to make mistakes—lots of them! You have permission to be gentle with yourself when you do. You have permission to not be at your best.

- You have permission to not know the answers. You have permission to not need to know the answers.

- You have permission to long for whatever you long for. You have permission to grieve whatever you are grieving. You have permission to claim and lean into joy every time the opportunity arises.

- You have permission to set down the thoughts and beliefs that aren’t serving you.

- You have permission to write your own permission slips.

On a personal and somewhat ironic note, I found this blog post difficult to write. I started, stopped, and scrapped my efforts more than once. I began feeling frustrated with myself for not just getting it done. Then I came to the realization that I was demanding perfection of myself. I was creating my own suffering by asking myself for too much. So I gave myself permission to write a just okay blog post rather than a great one.

I gave myself permission to make mistakes. Once I did this, the writing flowed, and the process became enjoyable. When we watch for them, these permission slip moments occur often—moments in which by simply allowing ourselves this or that shift, we can reduce our stress and suffering and increase our ease and happiness. PFIC serves up a hefty dose of clean pain. You have permission to lay down whatever dirty pain is accumulating on top of it.